identify what could be a possible reaction to stereotype threat.

Abstract

A substantial number of experimental studies on stereotype threat explores performance of girls in mathematics. Merely few full-bodied on gender differences favoring girls in language functioning. However, gender differences in a reading test in the Program for International Pupil Assessment are three times larger than in mathematics. Considerable research indicates that gender differences in accomplishment and academic attitudes are partly explained by stereotype threat. In this study, using structural equation modeling on representative data from a sample of schoolboys in three historic period cohorts, we examined the associations of repeated experiences of stereotype threat and 2 outcome variables: language accomplishment and domain identification with language arts. We demonstrated that working retentivity and intellectual helplessness were predicted by the level of stereotype threat. Moving beyond past work, we showed that the indirect effect explaining domain identification through intellectual helplessness was significant in older cohorts. Additionally, the indirect effect linking stereotype threat and language achievement through working retention was not significant in the oldest accomplice. In this group, language identification significantly predicted language achievement. These results offer a tentative support of our prediction nigh a cumulative effect of stereotype threat on domain identification. The nowadays study enriches a pocket-sized only growing body of literature examining stereotype threat in male person samples. Moreover, it identifies a new mediational path by which stereotype threat may be translated into lower domain identification and in turn lower language accomplishment.

Introduction and literature overview

Studies on gender differences in mathematical accomplishment seem to gain much more publicity in comparison to inquiry explaining the gender gap in reading, or more broadly in language skills (e.g., Stoet and Geary 2015). This is surprising as the gender gap in reading observed in data coming from the Plan for International Pupil Cess (PISA) is three times larger than the gender gap in mathematics (Stoet and Geary 2015). The gap, favoring girls, was present in samples coming from 70% of countries participating in PISA study in 2009 and it has grown over the by decade (Stoet and Geary 2015). Analyses conducted at the level of participating countries examining the sources of gender gaps have led to the conclusion that gender differences in bookish achievement were not related to political, economic, or social equality (Stoet and Geary 2015), merely rather to student's attitudes toward dissimilar academic domains (Stoet and Geary 2018).

Stereotype threat, divers as the activation of a negative stereotype about one's group in a testing state of affairs (Steele and Aronson 1995), may exist i of the factors contributing to the gender gap in school achievement (Steele and Aronson 1995; Spencer et al. 1999; Pansu et al. 2016). For case, the activation of a stereotype nigh girls existence weak at mathematics is likely to lower math test performance in female grouping. This stereotype activation may not touch on boys since it does not concern their gender group. Analogously, the activation of a stereotype about boys being weak at language arts, may lower their verbal exam performance, but non girls' perfomance. Stereotype threat not only affects test performance simply can also evoke more than negative attitudes toward stereotyped domains (Expert et al. 2012). This miracle has been increasingly investigated in a broad range of domains such as mathematics (e.1000., Aronson et al. 1999), intelligence (due east.1000., McKay et al. 2002), spatial orientation (due east.chiliad., Tarampi et al. 2016) and memory (due east.m., Chasteen et al. 2005). The consequence has been shown to occur especially when the tasks were hard (Spencer et al. 1999) or required new solving strategies (Carr and Steele 2009). Stereotype threat inquiry also suggests that the impact of negative stereotypes is not limited to minority groups, such as African American students in verbal skills (Steele and Aronson 1995) or women in mathematics (Spencer et al. 1999), but can be also observed in majority groups such as White men in mathematics (Aronson et al. 1999).

Explanations of test functioning deficits nether stereotype threat conditions refer to working memory impairments that sally as a result of negative beliefs and emotions activated by stereotypes about ane'due south group (Schmader et al. 2008). For example, empirical studies documented that negative stereotype activation reduced working memory capacity measured by an operational span task (Schmader and Johns 2003). Like results were obtained using measures of executive functions such as antisaccade task (Jamieson and Harkins 2007), Stroop-colour naming task (Richeson and Shelton 2003; Hutchison et al. 2013), or Go/NOGO job (Mrazek et al. 2011). Additional analyses showed that working memory capacity was a significant mediator of performance in mathematical tests in female samples (Schmader and Johns 2003), confirming its cardinal role in the mechanism of stereotype threat.

Although researchers have amassed a considerable trunk of testify to support the importance of studying stereotype threat, they mostly investigated minority samples (women or girls, African American or Latino students). Thus, much less is known most the experiences, correlates, and mechanisms of stereotype threat in boys' or men'southward samples, despite the worldwide evidence that boys' achievement in reading is much lower than that of girls. Additionally, very few studies examined the consequence of gender stereotypes in exact tests (Keller 2007; Seibt and Förster 2004). To our knowledge, there is just ane written report examining the furnishings of stereotype threat in reading performance (Pansu et al. 2016). In this study, in the stereotype threat condition, the test was presented as diagnostic of language abilities, and this subtle manipulation was sufficient to evoke gender stereotypes about boys being weak at linguistic communication. The present study extends this line of research by investigating the feel of stereotype threat separately in iii age cohorts of boys aged from xiv to 16 years.

Since the beginning of stereotype threat studies, it has been speculated that stereotype threat experience is not an isolated incident but rather information technology may echo over time (Steele and Aronson 1995). Be that as it may, lilliputian enquiry has tested the consequences of repeated experiences of stereotype threat on schoolhouse achievement and attitudes toward dissimilar subjects (e.g., Woodcock et al. 2012).

Chronic stereotype threat

A large body of research on stereotype threat has traditionally explored the impact of experimentally activated content of group stereotypes on exam performance and academic achievement. Equally a side-effect of experimental pattern, stereotype threat was perceived rather as a temporary phenomenon express to the experimental situation with its effects lasting equally long as the stereotype is cognitively activated. The hidden assumption was that the effects of stereotype threat were reversible. As such, when negative stereotype activation decreases, individual's cerebral resources should return to their initial level (see review: Schmader et al. 2008). Nosotros question this assumption and postulate that in educational settings a stereotype threat experience does not appear on a single occasion. Due to repeated instances of stereotype threat, its negative consequences may accrue over time. Consequently, it can be posited that these repeated experiences of stereotype threat may have quantitatively unlike effects on noesis and motivation compared to the ones triggered by a single stereotype threat incident.

The effects of repeated experiences of stereotype threat only recently have been gaining in importance (Woodcock et al. 2012; Kalokerinos et al. 2014). So far, at that place is only a scarcity of enquiry examining the correlates of chronic stereotype threat in educational settings. In one of these few studies, Woodcock et al. (2012) evidenced motivational deficits in Latino students who experienced stereotype threat during their scientific career. More than specifically, they observed a significant decline in intention to persist in science and in the level of scientific identification in this grouping of minority students. Domain disidentification too emerged more than strongly in the following years of the study, leading to last domain abandonment. This lack of identification with the scientific domain was interpreted as the effect of instances of coping with stereotype threat.

Although domain disidentification is a well-documented consequence of an acute stereotype threat (Steele and Aronson 1995; Major et al. 1998; run across review: Schmader et al. 2008) and has been demonstrated to exist a significant correlate of chronic stereotype threat (Woodcock et al. 2012), a potential mechanism of domain disidentification due to stereotype threat remains unclear. To fill up this gap, we suggest intellectual helplessness as a mediator linking chronic stereotype threat and lower domain identification.

Intellectual helplessness

Intellectual helplessness is a psychological state characterized by 2 types of deficits, cognitive and motivational. Cognitive deficits tin be described as an impairment of more complex processing (eastward.k., von Hecker and Sedek 1999). Motivational deficits, on the other hand, lead to impairments in intrinsic and instrumental motivation and/or lack of interest in the domain (Rydzewska et al. 2017; Sedek and McIntosh 1998). Every bit a result, intellectual helplessness may lead to lower school achievements and a lower involvement in a item schoolhouse subject.

The machinery explaining the emergence of intellectual helplessness is based on the cognitive burnout model of learned helplessness (e.g., Sedek and Kofta 1990; Kofta and Sedek 1998; von Hecker and Sedek 1999). This model assumes that when in problem-solving situations, individuals in general tend to spontaneously engage in systematic cognitive processing. In a typical, controllable situation this cognitive mobilization enables the usage of complex cognitive strategies such as finding important pieces of information, detecting task inconsistencies or integrating information into mental models. All these activities lead to an effective solution of a job at mitt. However, in uncontrollable circumstances, when the task at manus is not solvable or a instructor cannot explain the subject affair, such a effective approach cannot lead to a existent progress in cognitive processing. Consequently, afterwards prolonged cognitive mobilization without any substantial cognitive gain, a cognitive exhaustion phase appears. In school settings, the land of cerebral exhaustion is known every bit intellectual helplessness. Intellectual helplessness is a domain-specific state and then the level of intellectual helplessness in ane domain (e.yard., mathematics) tends to be weakly related to the level of intellectual helplessness in another domain (e.k., history) (Sedek et al. 1993).

Aims of the present study

Following Woodcock and colleagues' reasoning (2012), we posit that stereotype threat is a dynamic procedure and its effects accumulate over time. Corroborating a previous study on chronic stereotype threat in girls in mathematics (Bedyńska et al. 2018), we utilize a representative sample of secondary schoolhouse boys to examine a path model with chronic stereotype threat every bit an antecedent of achievement and identification with language arts. Similarly to the model proposed by Bedyńska et al. (2018), we test two parallel indirect effects involving working memory and intellectual helplessness.

The present study advances literature on chronic stereotype threat in two important means. Firstly, the cardinal aim of this report is to deliver a tentative evidence of the dynamics of chronic stereotype threat by analyzing the model described higher up in three age cohorts of xiv-, fifteen-, and xvi-year olds. We hypothesize that as experiences of stereotype threat repeat in educational settings, the cognitive and motivational effects of chronic stereotype threat are likely to be more than pronounced. This should exist especially truthful for motivational correlates of chronic stereotype threat such as intellectual helplessness and domain identification. Therefore, borrowing the logic from intellectual helplessness studies, nosotros assume that the indirect event linking chronic stereotype threat to domain identification through intellectual helplessness would exist stronger in older cohorts of boys. In contrast, predictions based on the intellectual helplessness studies atomic number 82 to the assumption that the cerebral mechanism based on working memory would be quite stable across age cohorts. Thus, the indirect effect with working memory equally a mediator should exist of a relatively similar magnitude in all age cohorts of boys.

Secondly, our aim is also to test the explanation formulated past Stoet and Geary (2018) for the weak link between gender gap in bookish achievement and political, economical or social equality in the PISA information. In their results, showing gender-equality paradox, researchers found that involvement in the domain is a factor that explains the persisting gender gap in more than gender-equal countries. Thus, nosotros decided to examine the link between domain identification and achievement in language arts. Nosotros predict that this association, beingness a dynamic motivational process, may be also stronger in older cohorts.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure

Information from 619 boys from three levels of classes in gender mixed secondary schools were analyzed in the study. There were 231 first age accomplice pupils (M historic period = 13.55, SD = 0.42), 204 south age cohort pupils (Chiliad historic period = 14.five, SD= 0.37), and 184 third age cohort pupils (G age = fifteen.54, SD = 0.38). The sampling process involved ii steps. In the starting time step, 24 secondary schools were randomly sampled with a stratification based on a region (two regions of the country) and school location (village, small-scale city, medium city). In the second step, classes were randomly selected from each school. All pupils belonging to the class were invited every bit participants. Around 5% of the selected pupils did not take part in the study due to their absence at schoolhouse, therefore 633 pupils took role in the study. The written report was presented as aimed at testing new online educational games. None of the children resigned from the participation during the written report.

The research protocol was approved past the Ethical Committee of the Educational Research Institute (Warsaw, Poland). The present report was conducted in compliance with upstanding standards adopted by the American Psychological Association (APA 2010). Appropriately, prior to participation pupils were informed near the general aim of the enquiry and the anonymity of their data. The participation was voluntary, and the pupils did not receive bounty for their participation in the study. Additionally, parents signed a written consent for their children to participate in the written report.

Information were collected during regular schoolhouse hours in a unmarried session that lasted 45 min. After explaining the aim of the study, pupils took a computerized working retentiveness test and and so online questionnaires which among others consisted of scales measuring chronic stereotype threat, intellectual helplessness, domain identity, language achievement and pupils' attitudes towards schoolhouse. All survey questions were administered in the native linguistic communication.

Measures

Chronic stereotype threat

Chronic stereotype threat scale was constructed of the scale proposed by Bedyńska and colleagues (2018). We rephrased the original vii items irresolute the focus of the calibration from mathematics to language. Examplary items of the scale are: 'Other pupils in my class experience that I accept a lower language power because of my gender', 'I worry that if I fail my instructor will attribute my poor operation to my gender', 'I worry that if I fail during a linguistic communication test, information technology will prove that all boys are poor at language'. Participants provided their answers on a half-dozen-signal scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to vi (strongly concord). To evaulate the level of chronic stereotyp threat, student responses were averaged to class a chronic stereotype threat index. Similarly to Bedyńska et al. (2018), the reliability of the scale was high (α = 0.88). The construct validity tested with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) indicated that the scale was unidimensional: Χ2 (12) = 60.848, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.976, TLI = 0.958, SRMR = 0.03, RMSEA = 0.081, ninety% CI (0.061, 0.101), p = 0.006.

Working memory

Working memory was measured with a computerized Functional Aspects of Working Memory Test (Sedek et al. 2016). The test consisted of three tasks that measured mutually related functions of working retention: simultaneous storage and processing, supervision, and coordination functions. Tasks involved visually bonny natural objects (ladybugs, balls, drawing-styled faces). The examination was used previously in educational research and proved its validity in predicting schoolhouse achievement (Sedek et al. 2016). The proportion of correct answers was the measure of working memory. Due to the heterogeneous nature of this test, the working memory measure was entered to the model as a latent variable, allowing the evaluation of the input of each of the tasks in the relation between predictor and outcome variables.

Intellectual helplessness

Intellectual helplessness was evaluated using nine items selected from the Intellectual Helplessness Scale (IHS, Sedek and McIntosh 1998). Boys were asked to assess on a 6-signal Likert type scale (ranging from i—never to half dozen—e'er) to what an extent they experienced intellectual helplessness symptoms during native language class. The statements described feelings and thoughts during native linguistic communication classes: 'I experience tired'; 'I feel helpless'. Similarly to the full version (Sedek and McIntosh 1998), the short version of the calibration was highly reliable (Cronbach's α = 0.90).

Linguistic communication achievement

We used Grade Point Average (GPA) values in language from 2 semesters before the report to measure achievement in language. GPA values were averaged. The higher value reflected college achievement, with i meaning not passing, and vi excellent.

Domain identification

Nosotros used a unmarried-item measure of domain identification ('It is important for me to be adept at language') adopted from the work of Aronson et al. (1999). Boys used a 6-point Likert type scale ranging from one (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) to rate the importance of the native language domain.

Information preparation and analytical arroyo

The multi-group structural equation modeling analyses were conducted using Mplus 7.iii (Muthén and Muthén 2015) with a grouping variable defining age cohort. We used Maximum Likelihood Robust (MLR) approach to bargain with continuous but not-normally distributed variables. Since all data were obtained in classes with boys beingness clustered by class membership, this nested structure was defined by using the function ANALYSIS = Circuitous in Mplus with course membership equally the cluster variable (Muthén and Satorra 1995). To prepare data for analyses, all classes smaller than three pupils were excluded (iv classes, seven participants) and seven pupils were excluded due to missing values on at least ane of the measured variables. Then, a preliminary charabanc model with three age groups modelled simultaneously was constructed with one predictor (chronic stereotype threat), two parallel mediators (intellectual helplessness and working retention) and two dependent variables: language achievement and identification with language. All indirect effects were evaluated using the INDIRECT function in Mplus. The aim of the latter was to examine intellectual helplessness and working memory equally potential mediators of the association betwixt chronic stereotype threat and language identification and achievement. We proposed two mediational paths of chronic stereotype threat to domain identification with language through (i) intellectual helplessness (2) working memory and three mediational paths from stereotype threat to language achievement through (i) intellectual helplessness, (2) working retentiveness, (3) intellectual helplessness and domain identification. All indirect furnishings were examined using 95% confidence intervals (CI) method with the indirect effect existence significant if the CI does not include zero (MacKinnon et al. 2002).

Evaluation of the structural model was based on robust Χtwo statistic and the Root Mean Foursquare Error Approximation (RMSEA), the Standardized Root Mean Foursquare Residue (SRMR), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) equally recommended by Kline (2011). Nosotros used the nearly widely recommended cut-off values indicative of adequate model fit to the information, respectively: RMSEA and SRMR < 0.06 and < 0.08, CFI and TLI > 0.95 and > 0.90 (Lance et al. 2006).

Results

Descriptive statistics

The relation between variables included in the model and the associated descriptive statistics for three levels of classes are shown in Table one. Mostly, in all three cohorts, chronic stereotype threat was positively correlated with intellectual helplessness, and negatively correlated with working memory.

Path model with working retention and intellectual helplessness as mediators

Evaluation of the model

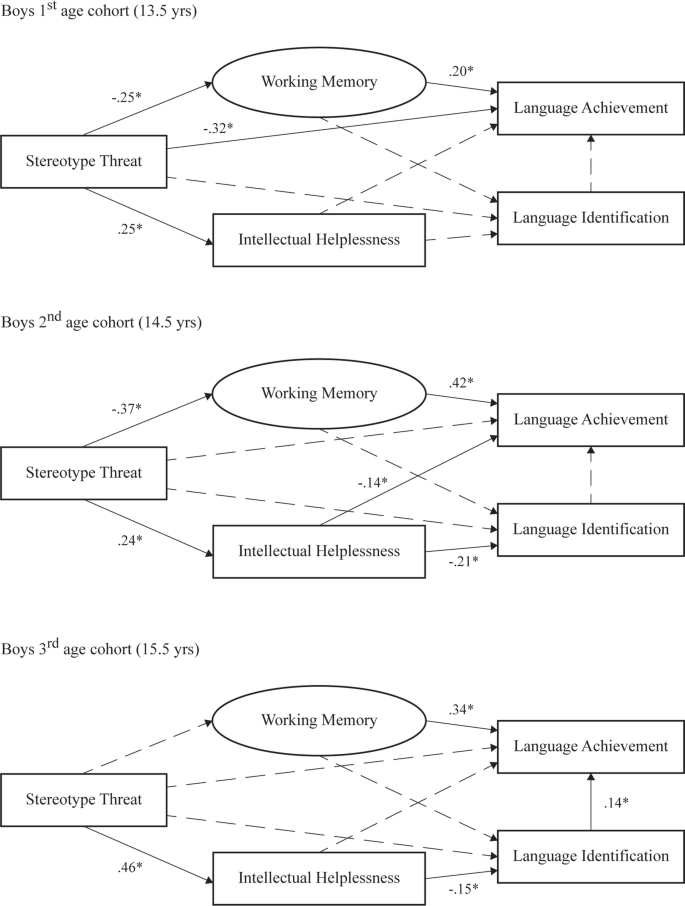

Results indicated that the model with intellectual helplessness and working memory as mediators (see Fig. 1) achieved a good fit to the information. The general test of fit for the model was non-significant Χtwo = 36.195, df = 35, p = 0.41. This general fit was also supported by the values of specific fit indices: CFI = 0.997, TLI = 0.995, RMSEA = 0.013, 90% CI (0.001, 0.052), p > 0.05 (p = 0.935). Only SRMR exceeded the acceptable value of good fit and was 0.133. The model explained around 2% of variability in domain identification with language (R 2 = 0.017) in the first age cohort, 5.5% (R 2 = 0.055) in the second historic period cohort, and 2% (R 2 = 0.020) in the third age cohort. For language achievement, 19% of variability was explained in the offset historic period cohort (R 2 = 0.194), 26% in the 2d historic period cohort (R 2 = 0.260), and 17% in the 3rd age cohort (R 2 = 0.169). Chi square contributions from each group were the post-obit: 8.699 for the first, 17.560 for the second, and 9.936 for the third cohort. The path coefficients for all three age groups are displayed in Table 2.

The full mediational models for three historic period cohorts predicting linguistic communication achievement and identification by chronic stereotype threat with two mediators: working memory, and intellectual helplessness. (Not-significant paths are indicated by dashed lines, while significant paths are indicated by solid lines; all coefficients are standardized solutions; p < 0.05)

Model for the first cohort (13.five years)

In the first age group, stereotype threat was negatively related to working retentivity and to language achievement. Working memory was positively associated with language achievement. The higher level of stereotype threat was also associated with a college level of intellectual helplessness. None of the variables was a significant predictor of domain identification with linguistic communication. To analyze the mediational role of working retention and intellectual helplessness, statistics for indirect furnishings were calculated. The assay of indirect furnishings showed that only one indirect effect was significant in this group—indirect effect from stereotype threat via working retention to language achievement β = − 0.049, p = 0.007 with CI (− 0.085, − 0.013).

Model for the second cohort (xiv.5 years)

A slightly different pattern of the relationships between the variables was obtained for pupils in the second historic period cohort. Once more, stereotype threat was negatively related to working memory and positively to intellectual helplessness. Both postulated mediators, intellectual helplessness and working memory, were related to language accomplishment—working retentiveness was correlated positively while intellectual helplessness negatively. Learned helplessness was a stronger predictor of domain identification in linguistic communication than of language achievement. Finally, 2 indirect furnishings were meaning: the indirect consequence via intellectual helplessness to language identification [(β = − 0.051, p = 0.013), CI (− 0.091, − 0.011)] and the indirect effect via working retentivity to language achievement [(β = − 0.152, p = 0.003), CI (− 0.253, − 0.051)]. The indirect effect of stereotype threat through intellectual helplessness to language accomplishment was significant at the level of statistical tendency (β = − 0.034, p = 0.062).

Model for the third accomplice (fifteen.v years)

Results for the tertiary historic period accomplice showed that stereotype threat was positively associated with intellectual helplessness but not with working retentivity. The latter variable was significantly related to language achievement. Domain identification was predicted negatively by intellectual helplessness. Although weak, in that location was also a relation between language identification and linguistic communication achievement. The simply significant indirect upshot explained language identification via intellectual helplessness [β = − 0.070, p = 0.040, CI (− 0.137, − 0.003)]. Although domain identification was significantly related to language achievement, this link was too weak to present equally a significant indirect event with two mediators: intellectual helplessness and domain identification linking stereotype threat and language achievement.

To sum upwardly, the path model examined in 3 age cohorts suggested that working memory was a meaning mediator of language accomplishment in younger groups only non in the oldest. In dissimilarity, the link between stereotype threat and domain identification in language was stronger in older cohorts but non in the youngest. It is also important to notice that the association betwixt stereotype threat and intellectual helplessness was the strongest in the oldest age group. In this group we can likewise start to observe a weak merely significant relation of domain identification and achievement in language.

Discussion

Bearing in mind that the experiences of stereotype threat appear repeatedly in educational settings, information technology is highly of import to understand psychological processes involved in the theoretical underpinnings of the adaptation to chronic stereotype threat. We believe that the present research substantially contributes to the debate on the dynamics of chronic stereotype threat and its mechanisms.

Start, we provided an answer to the theoretical and empirical question about a machinery that links chronic stereotype threat and domain identification with the achievement of boys in language arts. Corroborating previous findings which showed working memory to exist associated with chronic stereotype threat (Bedyńska et al. 2018), this written report proposes a preliminary empirical test of a new mechanism of domain identification based on intellectual helplessness. We plant that chronic stereotype threat is positively linked to intellectual helplessness which in plough is negatively related to domain identification with the native language. Thus, our results back up the prediction that intellectual helplessness may transmit an influence of chronic stereotype threat not only into mathematical underperformance of the minority grouping (Bedyńska et al. 2018) just also into disidentification with language observed in the bulk grouping. This outcome enhances the agreement of the processes underlying the lack of domain identification and domain abandonment observed in longitudinal studies on chronic stereotype threat in Latino and African American students (Woodcock et al. 2012).

Second, nosotros offering probably the first empirical comparison of two mediational paths presented in the literature, that is cerebral (working retentivity) and motivational (intellectual helplessness) deficits, in inducing lower domain identification. The results prove that although working memory capacity is related to chronic stereotype threat and language achievement, it is not a meaning mediator of domain identification. This can be interpreted as a preliminary evidence of two parallel and probably independent mechanisms leading to underachievement and the lack of identification with a domain. The question remains, withal, whether the underachievement tin be observed simply together with the domain disidentification or is it possible for students to show disidentification without underachievement. We hope that this initial evidence virtually these two processes existence separate will provide an inspiration for time to come enquiry.

Third, by testing the magnitude of the two mediational paths across three age cohorts, our work contributes to the understanding of the dynamics of the reactions to chronic stereotype threat. As mentioned before, the indirect effect involving working retention linking stereotype threat and language achievement was pregnant only in the youngest accomplice. This outcome suggests that the cognitive machinery is not sufficient in explaining identification with linguistic communication. A different blueprint emerged for intellectual helplessness which can be perceived as the motivational machinery. There was no meaning indirect human relationship between stereotype threat and language identification via intellectual helplessness in the youngest accomplice. Notwithstanding, this path turned out to exist meaning in the older cohorts. Such a design of results supports the hypothesis about the cumulative nature of the motivational mechanism of chronic stereotype threat based on intellectual helplessness and explains domain disengagement (Woodcock et al. 2012).

Limitations and boosted directions for future enquiry

The present findings should exist interpreted with respect to some limitations. First, linguistic communication identification was estimated with a single-item cocky-report measure. Although a single-detail measure is widely used in experimental research on stereotype threat (e.yard. Aronson et al. 1999; Stone 2002), different aspects of this cocky-schema may be evaluated, such equally the importance and likeability of the subject, having high abilities and achievement in the domain or enrolment in particular classes (Smith and White 2001). Hereafter enquiry should use more than complex measures with different dimensions of domain identification to provide a broader understanding of a pupil'due south educational choices.

Second, the study used a correlational and cross-sectional design, thus the ability to determine the directionality of the effects as well as their temporal club is express. Time to come enquiry should examine the relation between chronic stereotype threat and domain identification using longitudinal designs to define the modify in magnitude of the proposed mediational paths. Tertiary, the present written report would have benefited from additional information regarding participants' characteristics identified in previous inquiry as important moderators of stereotype threat, such as gender identification (Schmader 2002), stereotype endorsement (Schmader et al. 2004) or test feet (Tempel and Neumann 2014). Future investigation should consider examining or at to the lowest degree decision-making some of these variables.

Conclusions

Despite the aforementioned limitations, the present findings take important theoretical and practical implications. From the theoretical standpoint, they offer a meaningful insight into a novel machinery of chronic stereotype threat through intellectual helplessness—a reliable explanation of lower identification with a domain. The inclusion of this mediational path may be besides a valuable source of new hypotheses regarding the dynamics of accumulative changes in motivational and cerebral aspects of repeated experiences of stereotype threat.

The proposed mechanism is important as well for teachers and policy makers as it tin shape boys' interest in and a farther motivation to pursuit didactics in humanities and social sciences. Additionally, as language skills are highly correlated with mathematics and scientific discipline, they show their relevance for success in STEM domains (Stoet and Geary 2015).

References

-

APA (2010). Upstanding principles of psychologists and code of conduct. http://www.apa.org/ethics/lawmaking/. Accessed 10 Oct 2013.

-

Aronson, J., Lustina, M. J., Good, C., Keough, Chiliad., Steele, C. M., & Brown, J. (1999). When white men tin't practise math: Necessary and sufficient factors in stereotype threat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35(ane), 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.1998.1371.

-

Bedyńska, S., Krejtz, I., & Sedek, Thou. (2018). Chronic stereotype threat is associated with mathematical achievement on representative sample of secondary schoolgirls: The role of gender identification, working memory, and intellectual helplessness. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 428. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00428.

-

Carr, P. B., & Steele, C. Yard. (2009). Stereotype threat and inflexible perseverance in problem solving. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 853–859. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.003.

-

Chasteen, A. Fifty., Bhattacharyya, S., Horhota, M., Tam, R., & Hasher, Fifty. (2005). How feelings of stereotype threat influence older adults' memory functioning. Experimental Crumbling Research, 31(iii), 235–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/03610730590948177.

-

Expert, C., Rattan, A., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Why do women opt out? Sense of belonging and women's representation in mathematics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(4), 700–717. https://doi.org/ten.1037/a0026659.

-

Hutchison, K. A., Smith, J. L., & Ferris, A. (2013). Goals can exist threatened to extinction using the Stroop task to clarify working memory depletion under stereotype threat. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(ane), 74–81. https://doi.org/ten.1177/1948550612440734.

-

Jamieson, J. P., & Harkins, S. Chiliad. (2007). Mere endeavor and stereotype threat performance effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(4), 544–564. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.4.544.

-

Kalokerinos, East. 1000., von Hippel, C., & Zacher, H. (2014). Is stereotype threat a useful construct for organizational psychology research and practice? Industrial and Organizational Psychology, vii(3), 381–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/iops.12167.

-

Keller, J. (2007). Stereotype threat in classroom settings: The interactive upshot of domain identification, chore difficulty and stereotype threat on female students' maths performance. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(2), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709906x113662.

-

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and do of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

-

Kofta, M., & Sedek, K. (1998). Uncontrollability as a source of cognitive exhaustion: Implications for helplessness and depression. In M. Kofta, M. Weary, G. Sedek, M. Kofta, K. Weary, & G. Sedek (Eds.), Personal control in action: Cognitive and motivational mechanisms (pp. 391–418). New York, NY: Plenum Press. https://doi.org/ten.1007/978-i-4757-2901-6_16.

-

Lance, C. E., Butts, Thousand. M., & Michels, L. C. (2006). The sources of four ordinarily reported cutoff criteria what did they actually say? Organizational Research Methods, 9(2), 202–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428105284919.

-

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, Five. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83–104. https://doi.org/ten.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4.

-

Major, B., Spencer, Southward., Schmader, T., Wolfe, C., & Crocker, J. (1998). Coping with negative stereotypes about intellectual performance: The office of psychological disengagement. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(ane), 34–l. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167298241003.

-

McKay, P. F., Bowen-Hilton, D., & Martin, Q. D. (2002). Stereotype threat effects on the raven advanced progressive matrices scores of African Americans. Journal of Practical Social Psychology, 32(4), 767–787. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00241.10.

-

Mrazek, Thousand. D., Chin, J. M., Schmader, T., Hartson, K. A., Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. Westward. (2011). Threatened to distraction: Mind-wandering as a consequence of stereotype threat. Periodical of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(6), 1243–1248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.05.011.

-

Muthén, B. O., & Satorra, A. (1995). Complex sample data in structural equation modeling. In Sociological Methodology (Ed.), p (Vol. Marsden, pp. 267–316). Washington, DC: American sociological. https://doi.org/10.2307/271070.

-

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2015). Mplus user's guide. Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén.

-

Pansu, P., Régner, I., Max, S., Colé, P., Nezlek, J. B., & Huguet, P. (2016). A brunt for the boys: Evidence of stereotype threat in boys' reading operation. Periodical of Experimental Social Psychology, 65, 26–30. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.jesp.2016.02.008.

-

Richeson, J. A., & Shelton, J. N. (2003). When prejudice does non pay furnishings of interracial contact on executive office. Psychological Scientific discipline, xiv(3), 287–290. https://doi.org/ten.1111/1467-9280.03437.

-

Rydzewska, 1000., Rusanowska, Grand., Krejtz, I., & Sedek, G. (2017). Uncontrollability in the classroom: The intellectual helplessness perspective. In One thousand. Bukowski, I. Fritsche, A. Guinote, & M. Kofta (Eds.), Coping with the lack of command in the social world (pp. 62–79). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

-

Schmader, T. (2002). Gender identification moderates stereotype threat effects on women's math performance. Periodical of Experimental Social Psychology, 38(2), 194–201. https://doi.org/ten.1006/jesp.2001.1500.

-

Schmader, T., & Johns, M. (2003). Converging evidence that stereotype threat reduces working memory capacity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(iii), 440–452. https://doi.org/x.1037/0022-3514.85.3.440.

-

Schmader, T., Johns, M., & Barquissau, M. (2004). The costs of accepting gender differences: The part of stereotype endorsement in women's experience in the math domain. Sexual practice Roles, 50(11–12), 835–850. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:sers.0000029101.74557.a0.

-

Schmader, T., Johns, Chiliad., & Forbes, C. (2008). An integrated procedure model of stereotype threat effects on operation. Psychological Review, 115(2), 336–356. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.115.2.336.

-

Sedek, 1000., & Kofta, M. (1990). When cerebral exertion does not yield cognitive gain: Toward an informational explanation of learned helplessness. Periodical of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 729–743. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.four.729.

-

Sedek, Yard., Kofta, G., & Tyszka, T. (1993). Effects of uncontrollability on subsequent determination making: Testing the cognitive burnout hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 1270–1281. https://doi.org/ten.1037/0022-3514.65.6.1270.

-

Sedek, G., Krejtz, I., Rydzewska, K., Kaczan, R., & Rycielski, P. (2016). Iii functional aspects of working retentivity as potent predictors of early school achievements: The review and illustrative evidence. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 47(1), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1515/ppb-2016-0011.

-

Sedek, G., & McIntosh, D. North. (1998). Intellectual helplessness: Domain specificity, teaching styles, and school achievement. In Grand. Kofta, Yard. Weary, & G. Sedek (Eds.), Personal control in activity: Cognitive and motivational mechanisms (pp. 391–418). New York: Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-2901-6_17.

-

Seibt, B., & Förster, J. (2004). Stereotype threat and operation: How self-stereotypes influence processing by inducing regulatory foci. Periodical of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(1), 38–56. https://doi.org/x.1037/0022-3514.87.ane.38.

-

Smith, J. L., & White, P. H. (2001). Evolution of the domain identification measure: A tool for investigating stereotype threat effects. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 61(six), 1040–1057. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131640121971635.

-

Spencer, S. J., Steele, C. M., & Quinn, D. M. (1999). Stereotype threat and women's math functioning. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35(1), 4–28. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.1998.1373.

-

Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 797–811. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.five.797.

-

Stoet, G., & Geary, D. C. (2015). Sex differences in academic achievement are not related to political, economic, or social equality. Intelligence, 48, 137–151. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.intell.2014.eleven.006.

-

Stoet, G., & Geary, D. C. (2018). The gender-equality paradox in science, technology, applied science, and mathematics pedagogy. Psychological Science, 29(4), 581–593. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617741719.

-

Stone, J. (2002). Battling doubt past avoiding practise: The effects of stereotype threat on self-handicapping in white athletes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(12), 1667–1678. https://doi.org/x.1177/014616702237648.

-

Tarampi, M. R., Heydari, N., & Hegarty, G. (2016). A tale of two types of perspective taking sex differences in spatial ability. Psychological Science, 27(11), 1507–1516. https://doi.org/ten.1177/0956797616667459.

-

Tempel, T., & Neumann, R. (2014). Stereotype threat, examination feet, and mathematics performance. Social Psychology of Education, 17(3), 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-014-9263-9.

-

von Hecker, U., & Sedek, G. (1999). Uncontrollability, depression, and the construction of mental models. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(4), 833–850. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.4.833.

-

Woodcock, A., Hernandez, P. R., Estrada, M., & Schultz, P. (2012). The consequences of chronic stereotype threat: Domain disidentification and abandonment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(4), 635–646. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029120.

Funding

The present study was a part of the arrangement level project "Quality and effectiveness of education—strengthening institutional research capabilities" executed by the Educational Inquiry Institute and co-financed by the European Social Fund (Man Upper-case letter Operational Programme 2007–2013, Priority III Loftier quality of the pedagogy system).

Writer data

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Ideals declarations

Disharmonize of involvement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher'due south Notation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits employ, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatever medium or format, equally long equally you lot give appropriate credit to the original writer(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Commons licence, and indicate if changes were fabricated. The images or other 3rd party material in this commodity are included in the commodity'south Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is non included in the article'south Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted past statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted apply, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a re-create of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

Near this article

Cite this article

Bedyńska, S., Krejtz, I., Rycielski, P. et al. Stereotype threat as an antecedent to domain identification and achievement in language arts in boys: a cross-exclusive written report. Soc Psychol Educ 23, 755–771 (2020). https://doi.org/ten.1007/s11218-020-09557-z

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Consequence Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1007/s11218-020-09557-z

Keywords

- Stereotype threat

- Language identification

- Linguistic communication achievement

- Working memory

- Intellectual helplessness

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11218-020-09557-z

0 Response to "identify what could be a possible reaction to stereotype threat."

Publicar un comentario