Florence Italy Arte De Medici E Degli Spezial a Vallecchi 1922

one. Introduction

Gilding is an ornamental ornament in paintings which consists of applying a very sparse layer of golden (the gold leaf) using different techniques. Gilding was a very widespread technique in medieval fine art, specially in the Byzantine and Renaissance periods, where the aureate leaf was used in paintings on wooden panels to heighten the visual outcome of the saints' halos. Moreover, in the middle ages, many paintings were executed using the golden leaf as a background (gold ground). Usually, the gold in gildings was used pure only gilded alloys also as alloys simulating the colour of gold accept been also found. In this respect, the "oro di metà" (halfway) gilding was used mainly in Italy from the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries simply its structure and composition nevertheless remain unclear.

In the painting of the fifteenth century by the Chief of St. Ivo depicting Due south. Peter between St. Anthony Abbot and St. Mary Magdalene, the "oro di metà" gilding represents a rare example of its splendid state of preservation, which makes it ane of the few cases that has come to us then intact. Moreover, this gilding was applied according to both the most common execution techniques at that time: "a guazzo" (water gilding) on the background and "a missione" (gilding with mordant) on the borders of the garments. Briefly, in the water gilding, the gold foil is laid onto an adhesive layer consisting mainly of world pigments mixed with a protein binder (every bit egg-white and rabbit gum) and with some water commonly known as "bole", over gypsum ground. The bole gives a warm color to the gold equally well existence a cushion for successive treatments as for example burnishing and punching [1]. On the contrary, in the gilding with mordant, the gold foil is laid on an oil-based mordant unremarkably made of linseed oil mixed with pigments as driers. This technique is specially suitable for decorations and small details [ane].

The term "oro di metà" or "oro mezzo" was explicitly used by Cennini [2] describing different gilding techniques and warning confronting the tarnishing of silver which is a constituent of this type of gilding. Actually, the employ of "oro di metà" foils was very widespread in Tuscany since the end of the thirteenth century, and then much so that in the years 1315–1316 when the painters were admitted to the guild of the "Arte dei Medici eastward degli Speziali" (the guild of doctors and pharmacists) of Florence, in the statute is mentioned the "aurum di metà" regarding the penalties for those who were using it instead of fine gold without declaring information technology [iii]. Throughout the fourteenth century until the end of the fifteenth century, the "oro di metà" is observed in the gilding of some paintings past Jacopo del Casentino, Pacino di Buonaguida, Bernardo Daddi, and Puccio di Simone [4]; Neri di Bicci as well in his "Ricordanze" [5] certifies the use of "oro mezzo" on many "anticha" altar plates reporting even the cost, which is nigh one-half of that of the fine gilded [6]. As prescribed by the Florentine Statutes of 1396 and 1403 [7,viii,ix], the "oro di metà" foil results to take the same dimensions as that of silver; therefore, analyzing the costs [x], with the price of 100 pieces of fine gold, approximately 200 pieces of "oro mezzo" could be obtained with a size ranging from viii.3 to 7.three cm2.

Despite the existence of these very important historical documents which would suggest the utilize of ii different foils (one of silvery and one of gold) cast equally a "sandwich", in the nineteenth century, Merrifield and Eastlake [8] translated the "oro di metà" equally "gold that is much alloyed" like to other translators that used the expression "gold alloy". Similarly, Milanesi in 1859 introduced the meaning "oro falso battuto" (fake beaten gold) along with other translators that referred to "oro di metà" equally a gilded leafage that is "false" or "only half genuine" without giving neither whatever specifications nor the correct importance to this artistic executional technique.

An overview of all the definitions, meanings and assumptions ascribed to the expression "oro di metà", over the centuries, is precisely described by Skaug [viii]. However, we would like to give detail emphasis to the metal leaf commonly used in the European middle ages and known in French as "or parti", in dutch every bit "partijtgoud" and in german "gedeelt Golden" which share with "oro di metà" an etymological innuendo to a real divided structure.

In this piece of work, the observation carried out by means of both a polarized light optical microscope (OM) and an Ultra-High Resolution Scanning Electron Microscope (UHR-SEM) take confirmed, as far every bit nosotros know for the outset fourth dimension, the presence of two distinct very thin metallic foils with unlike thicknesses in the "oro di metà" gilding. Moreover, Energy Dispersive X-Ray (EDX) analysis has allowed for characterizing the composition of the gilt and silverish layers which take been institute out to be separated and overlapped besides equally identifying the degradation products of the argent layer responsible for the blackening process. Finally, complementary vibrational spectroscopic techniques such as micro-ATR-FTIR and micro-Raman spectroscopy were used in lodge to characterize the molecular composition of the "bole" as well as the preparation layers.

History of the Painting

Fragmentary and incomplete is the information regarding the painting of the Master of St. Ivo. Notwithstanding, Bernacchioni and Tartuferi [eleven,12] have been able to detect out some important information to trace its origin and history.

In 1895, the painting was at the collection of the Banca Popolare di Genova and information technology was auctioned at the Sangiorgi Gallery in Rome. This is the oldest piece of data on the provenance of this painting. Then, it was divided into 3 pieces.

Nonetheless, the inscription on the base of the S. Peter throne says that the woods panel painting was commissioned by Piero di Giovanni Ringli in 1438 when he was the castellan assigned by the Sforza as captain of the garrison to defend and command the Fortress of Avenza, a pocket-size village in Lunigiana (Tuscany, Italy), from Genova's ability. In support of this, the presence of the coat of arms of the diocese of Luni with the horns of the moon pointing upwardly, refers to Lunigiana. The historical and political context of that period suggests the church of Avenza equally a possible place of provenance of the painting. In particular, from 1437 to 1441, before returning to Genoa'southward control, Avenza was under the control of the Republic of Florence, thus explaining the presence of a painting made by the Florentine painter the Master of St. Ivo in that region.

The painting underwent just one restoration intervention in the early twentieth century, consisting of the separation of the triptych into three separated panels, their framing likewise as the pictorial recovery of the draperies. Moreover, the painting was in a private American collection from the early on twentieth century until 1993 and subsequently was put upwards for sale twice without undergoing further restorations.

Thus, this painting represents a very exceptional example in terms of conservation because it is devoid of previous interventions of cleaning and then much that the original varnish is still nowadays on the surface.

ii. Sampling, Samples Preparation and Methodology

Eleven samples were taken from the painting by using a scalpel in order to gather information on many issues about the technical execution and composition of gildings, painting layers, and the ground (preparation layer). The fragments were cast in epoxy-resin, dried and finely polished for the cross-sections preparation. In particular, polishing was carefully carried out using discs at dissimilar mesh (800-g-1200-4000) in order to perform the process very delicately. The stratigraphies were then observed past reflected polarized light OM and by an UHR-SEM. The elemental composition of unlike layers was provided by means of EDX spectroscopy; whereas, the molecular composition was provided by using micro-ATR-FTIR and micro-Raman spectroscopy.

Figure 1 shows a panoramic view of the entire painting along with the sampling points. The cross-department described in this work was taken from sampling area highlighted in bluish colour. After microscopic observation, this sample was considered crucial for the interpretation and the assessment of the gilding technical execution with respect to other samples where gildings were either in a bad conservation state or completely gone.

Optical microscopy observation was carried out using the polarised low-cal microscope Eclipse 150 by Nikon provided with 5 different magnification objectives (v×, ten×, 20×, 50× and 100×).

SEM-EDX observation and measurements were carried out at the Center of Electronic Microscopies "Laura Bonzi" (Ce.Yard.Eastward-CNR) by using an UHR-SEM Gaia iii FIB/SEM by Tescan which represents a step forward in the field of avant-garde electron microscopy. The electronic beam of this microscope enables the possibility of imaging at the "nano" scale level (upwards to 0.7 nm at fifteen keV), even with samples sensitive to electron beams such equally the majority of cultural heritage materials. The limit of detection of the EDX semi-quantitative analysis falls into the range of 0.two–i w% depending on the specific elements.

FT-IR spectra of the red sample were collected with a FT-IR spectrometer Agilent Technologies Cary 660 coupled with Cary 620 Microscope, equipped with a MCT detector. The spectra were acquired in ATR mode with Germanium crystal, collecting 64 scans, with a resolution of 4 cm−i in the 4000–400 cm−ane range. Spectra were processed using Agilent Resolutions Pro software.

Raman measurements were performed under an XPlora Horiba micro-Raman instrumentation equipped with three laser excitation sources. In particular, spectra of the ground layer were carried out using a 785 nm laser wavelength, a 100× objective, and diffraction grating of 1200 1000/mm. The spectra were collected using an accumulation time of 20 south.

iii. Results and Discussion

3.1. OM results

Figure 2 shows polarized OM images of the gilt surface of sample earlier the cantankerous-section preparation.

The presence of gold on the surface is clearly observable forth with cracks which permit the view of both a greyish layer underneath the gilt (the silver layer) likewise equally a red layer (the "bole") farther below. Moreover, on the surface, black spots are appreciable probably due to the degradation of the silver layer.

Figure 3 shows the microscope images of the cross-section at ii different magnifications (twenty× and 100× objectives). The white-coloured training layer with a thin (circa xxx–forty µm) "bole" layer on summit is clearly visible. The gilded layer is very sparse (1–2-micrometers) and shows a lack of uniformity due to either the degradation itself or to the polishing procedure. Where the gilded layer is very delicate, polishing could clean information technology away, although the process was carried out in a very delicate manner. The role of the cross-department which gave the clearest view of the gilt layer is shown in the prototype acquired using the highest magnification (100×). This part was observed at SEM and analysed by EDX spectroscopy. For this purpose, the sample was coated with a very thin layer of graphite.

3.2. SEM-EDX results

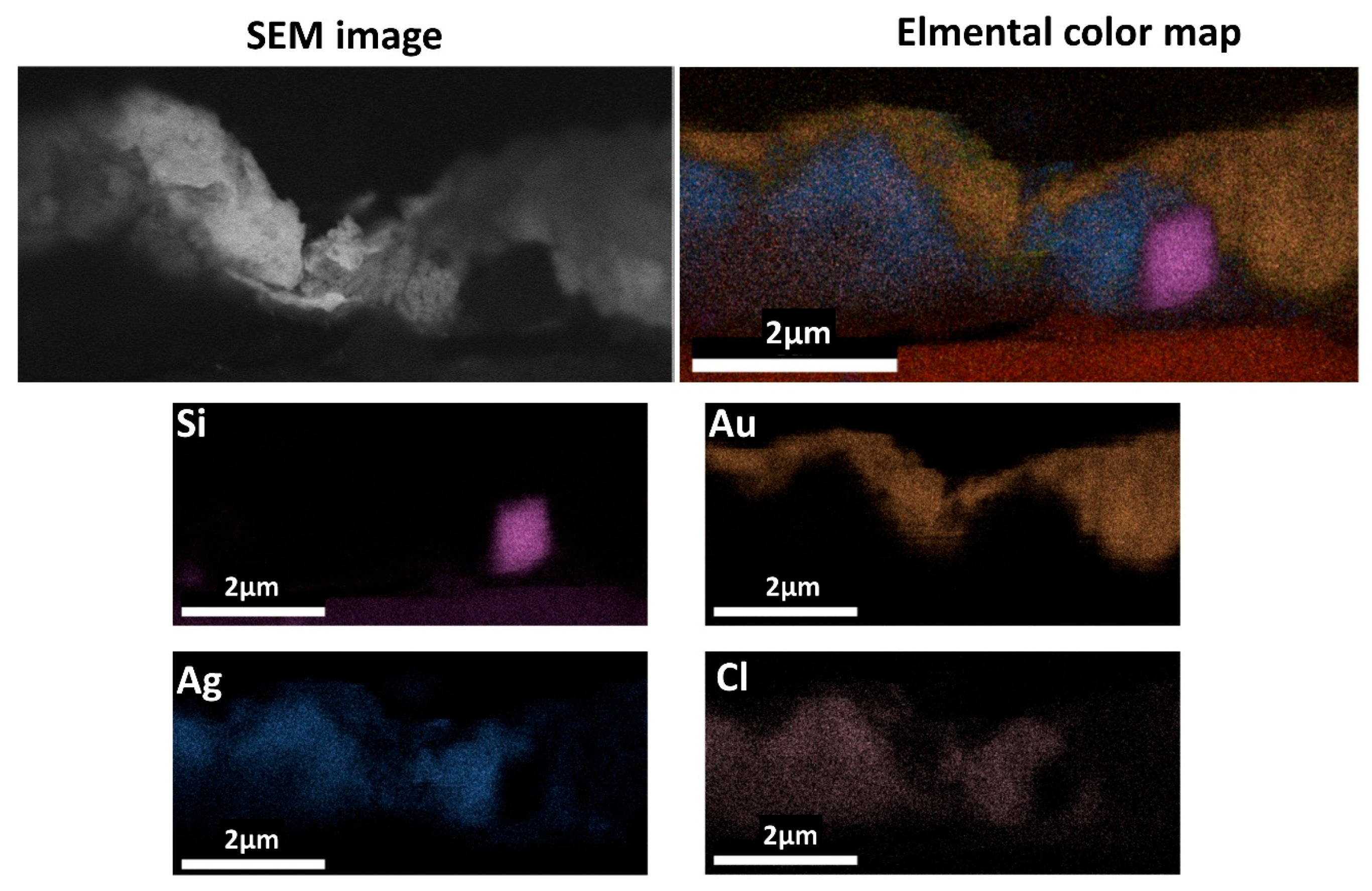

Back-Scattered Electrons (BSE)-SEM images (Figure iv) confirmed the presence of a very thin layer of metallic (of about ii µm of thickness). The metal layer appears to be constituted by two different elements (Figure 4c): the uppermost layer with a greater atomic number (brighter at SEM) and a 2nd layer, below the former one, with a lower atomic number. Moreover, in some parts, the distribution of the uppermost layer was not straight but folded covering the lower layer (Figure 4b).

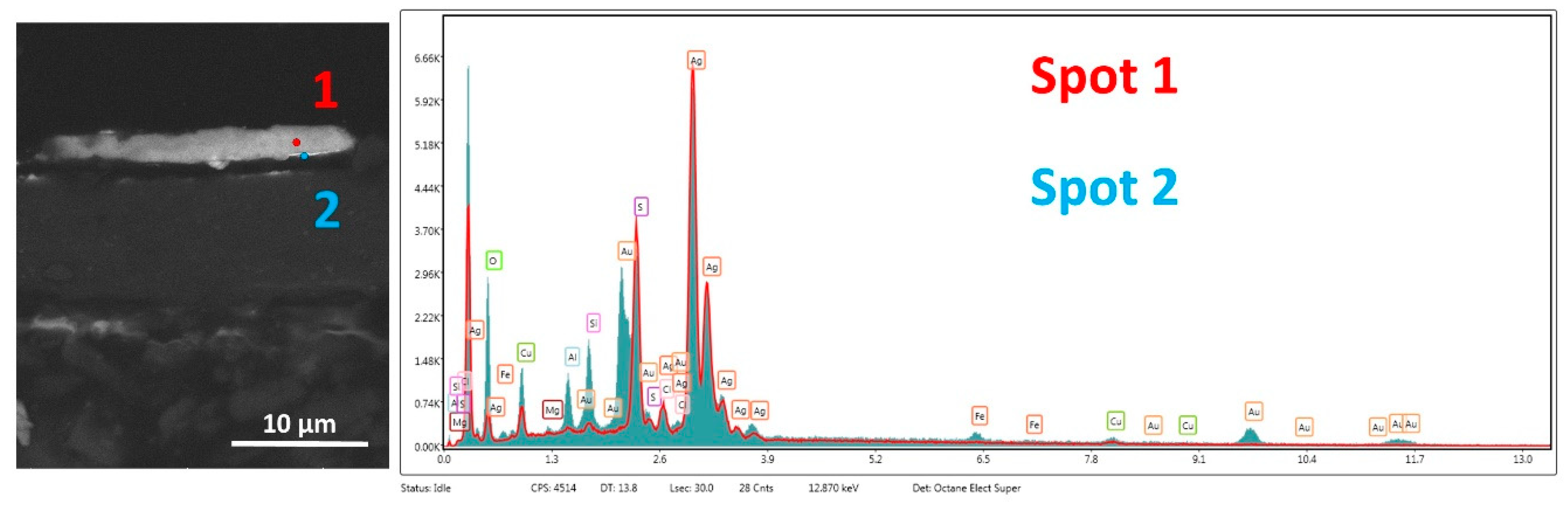

In order to place the composition of both the layers, EDX analysis was performed. The image of the two measuring points equally well as the results of the compositional assay are shown in Figure v. The results of the analysis highlighted that "spot 1" (carmine color) is constituted mainly by gilt (Au: 59 w%); whereas in "spot 2" (blue colour), silverish (Ag: 42 w%) is the major component. The quantification of carbon (C) and oxygen (O) might be affected past the resin and coating. However, the higher percentage of oxygen in the argent layer (28 w%) with respect to the gilded (x w%) might exist due to argent oxidation. Copper (Cu) is present as an impurity in the gold layer [13]. Moreover, the presence of iron (Fe) is ascribable to the "bole" composition, whereas elements as silicon (Si), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca) and aluminium (Al) come from the ground. The results of the semi-quantitative elemental analysis are summarized in Table 1.

In order to extend our knowledge of the distribution of chemical elements in a more extended area, a EDX compositional map was performed. Figure 6 shows differences in the distribution of gold, which is mainly distributed on the surface (see Au elemental map in Figure 6), and of argent, which appears to be underneath the gilded layer (run across Ag elemental map in Figure half-dozen). The "violet" squared grain is ascribable to the presence of quartz given that it is constituted mainly by silicon. Finally, we specially focused our attending on the presence of chlorine (Cl) in correspondence with silver. This can be reasonably ascribed to corrosion furnishings of silver due to sea cakewalk since the painting resided for a long time in Genova.

The combination of SEM images with EDX assay confirmed that the "oro di metà" gilding under study is constituted by 2 divided layers of silver and gold. However, in order to better the representation and reliability of the results obtained, another signal of the gilding was analyzed. In this respect, Figure 7 bear witness the BSE-SEM image and correlated EDX elemental analysis of another region of the gilding. In this case, not but the presence of two divided layers is further confirmed, simply some considerations regarding the thickness can be made as well. As indeed documented by Merzenich [ix], the fine gold foliage at that fourth dimension should take had a thickness of 0.25 µm and that of silverish three times as much. These dimensions and proportions seem to be confirmed in this case and it would be the start time that scientific evidence on this issue is provided.

Once again, EDX elemental analysis results confirmed the presence of aureate and silver in the ii layers. In particular, in "spot 1", weight percentages of gilt and silver of respectively 76 and 15 versus percentages in "spot 2" of 81 for silver and most "null" for gilt were achieved, further demonstrating the theory of the divided layers.

Finally, this study wanted to contribute to bringing about more clarity regarding the mechanisms of degradation of the silvery layer and the corrosion products forming in the tarnishing process mentioned by Cennini. In this respect, the BSE-SEM prototype of Figure 8 shows a big homogeneous mass growth over the very sparse gilded layer.

EDX spectroscopic analysis performed in the body of the mass (spot 1) shows very intense peaks of argent and sulphur (S) which suggests the presence of silver–sulphide (probably AgiiS), normally establish as degradation product of silver. Every bit was observed past Selwyn, sulphides grow through pores and produce dark spots that tin can spread over the gold layer [14]. Moreover, Ag2S is black in colour, explaining the presence of dark stains on the surface of the gilding every bit shown in Figure 2a. Information technology is worth noticing that the EDX spectrum in "spot 1" did not prove peaks characteristic of golden which were instead reasonably observed and quantified (19 w%) in the spectrum acquired in "spot ii" given that the spot of assay was taken over the thin gold layer. This again confirms that the "oro di metà" gilding is not an alloy.

3.3. Molecular spectroscopy results

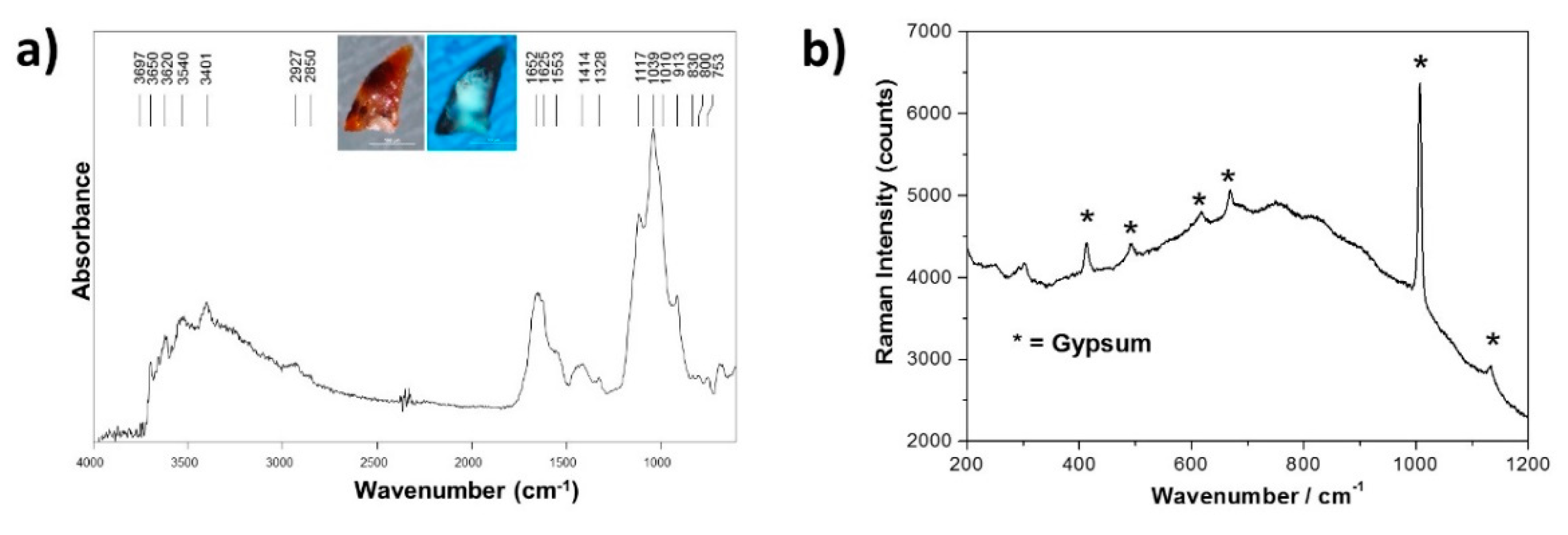

The characterisation and identification of the molecular limerick of the "bole" and the basis layer of the cross-section were achieved using micro-ATR-FTIR and micro-Raman spectroscopy, respectively. The analyses were carried out on a small flake of the sample without any training. For the "bole" analysis, ATR-FTIR spectroscopy was preferred to Raman in guild to avoid the stiff fluorescence background probably due to either the resin or the layer itself. ATR-FTIR and Raman spectra are shown in Effigy 9.

The micro-ATR FTIR punctual analysis of the red layer (Figure 9a) suggested the presence of a clayey pigment, such as ochre rich in kaolinite. Indeed, the typical hydroxyl ion bands of aluminosilicate kaolinite were found at 3697, 3650 and 3620 cm−i, while the Si–O–Si and Si–O–Al bands were visible at 1039 cm−one and 1010 cm−1, respectively [15].

In improver, calcium sulphate dihydrate was detected, which is consistent with the presence of gypsum in the ground (O-H stretching bands at 3540 and 3401 cm−one, bending vibration of water at 1625 cm−1 and vibration of sulphate at 1117 cm−i). The 1650 and 1553 cm−i bands of amide I and amide Ii, respectively, suggest the presence of a proteinaceous substance which could be egg white since information technology was commonly used at that fourth dimension for the preparation of the "bole" [16]. The absence of fluorescence (insets in Figure 9a) supports the use of clay.

Differently, Raman spectrum of the ground layer (Figure 9b) shows characteristic bands of Gypsum at 412, 492, 617, 670, 1007 and 1131 cm−one.

4. Conclusions

In this work, the divided construction of gold and silver layers in the "oro di metà" gilding of the fifteenth-century was scientifically demonstrated for the starting time fourth dimension. The use of terminal-generation SEM-EDX instrumentation was crucial for this approach allowing the imaging and analysis of very thin (under micron) layers separately. Elemental colour mapping of the gilding was too performed confirming the divided construction of the metallic layers. Moreover, from BSE-SEM images, an interpretation of the dissimilar thickness of golden and silver was provided forth with the confirmation, for the outset time, of their hypothetical employ in relation ane/3.

The advantage of overlapping two separated layers of gold and silvery with respect to an alloy was essentially artful. Every bit soon as it was fabricated, this gilding used to be so bright that it could have been mistaken for pure gold. On the contrary, the golden/silver blend, used since ancient times (in minting for case), did not accept the same effect but a common cold color instead.

Besides, in this work, considerations regarding the tarnishing and degradation mechanism of the silver layer were fabricated. The transformation of silver in silverish–sulphide equally a corrosion product was likewise demonstrated. Finally, the use of vibrational spectroscopies at the micro level such as Raman and ATR-FTIR allowed the molecular identification of the mineral phases constituting the "bole" as well as the ground layer.

Writer Contributions

Conceptualization: I.O. and L.M.; Methodology: I.O.; Investigation: I.O., M.B., P.Yard., 50.C., A.L. and B.S.; Resources I.O., 50.Thou.; M.B., P.Chiliad., L.C., A.50., B.S. and S.South.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: I.O.; Writing—Review & Editing, I.O., L.G., L.C., M.B., P.Chiliad. and B.S.; Visualization: I.O.; Supervision: I.O. and L.One thousand.; Project Administration: I.O. and L.Chiliad.; Funding Acquisition: Due south.S.

Funding

This research was funded past European project IPERION-CH "Integrated Platform for the European Research Infrastructure on Cultural Heritage" (H2020-INFRAIA-2014-2015, Grant Agreement n. 654028.

Acknowledgments

A special thank you to Matteo Salamon (Salamon Gallery, Milan, Italia) for his courtesy and support in this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sandu, I.C.A.; Afonso, L.U.; Murta, Due east.; de Sa, M.H. Gildings techniques in religious art betwixt east and west, 14th–18th centuries. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2010, one, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Cennini, C. Il Libro dell'Arte a cura di Franco Brunello; Pozza, N., Ed.; Vicenza, Italy, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Ciasca, R. Statuti Dell'arte dei Medici east Speziali Nella Storia e nel Commercio Fiorentino; Stabilimenti Grafici Editoriali di Attilio Vallecchi: Firenze, Italy, 1922; p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, L. Osservazioni e studi effettuati sulle opere appartenenti alla Collezione Alana di New York. Private Archive of Gallo Restauro Studio, 2005–2019. [Google Scholar]

- Santi, B. Neri di Bicci; Le Ricordanze: Pisa, Italy, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Doren, A. Le arti Fiorentine; Firenze, Italy, 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Bomford, D.; Dunkerton, J.; Gordon, D.; Roy, A. Fine art in the Making, Italian Painting before 1400; National Gallery: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Skaug, E. Cenniniana: Notes on Cennino Cennini and His Treatise; Arte Cristiana: Milan, Italia, 1993; pp. 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Merzenich, C. Dorature eastward policromie delle parti architettoniche nelle tavole d'altare toscane fra Trecento e Quattrocento. Kermes 1996, 26, 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Skaug, E. Contributions to Giotto's Workshop. JSTOR 1971, 15, 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Bernacchioni, A. The Ringli Triptych—A New Discovery by the Chief of St. Ivo; Salamon, C., Ed.; Milan, Italian republic, 2019; pp. 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tartuferi, A. The Ringli Triptych—A New Discovery past the Chief of St. Ivo; Salamon, C., Ed.; Milan, Italy, 2019; pp. 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, Fifty. Manuale delle Tecniche di Restauro- le Dorature e le Lacche; EDUP: Roma, Italia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Selwyn, 50. Corrosion Chemistry of Gilded Silver and Copper; OSG Postprints: Miami, FL, U.s., 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Genestar, C.; Pons, C. World pigments in painting: Characterisation and differentiation by means of FTIR spectroscopy and SEM-EDS microanalysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2005, 382, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meilunas, R.J.; Bentsen, J.G.; Steinberg, A. Assay of Anile Pigment Binders by FTIR Spectroscopy. Stud. Conserv. 1990, 35, 33–51. [Google Scholar]

Figure ane. Panoramic view of the painting by the Master of St. Ivo and the sampling points. Dimensions of the painting: 133.8 × 149.2 cm. The cross-section described in this piece of work was taken from the sampling area highlighted in blue colour.

Effigy 1. Panoramic view of the painting past the Master of St. Ivo and the sampling points. Dimensions of the painting: 133.8 × 149.2 cm. The cantankerous-section described in this work was taken from the sampling area highlighted in blueish colour.

Figure ii. Polarized OM images (10× magnification) of the surface sample with cross (a) and airplane (b) polarized light. Figure 2a was acquired with cantankerous polarized light in gild to highlight the red colour of the "bole" underneath the gilded layer; whereas, Figure 2b was acquired with plane polarized light in order to highlight the gilded surface.

Figure two. Polarized OM images (10× magnification) of the surface sample with cantankerous (a) and plane (b) polarized calorie-free. Figure 2a was acquired with cross polarized light in order to highlight the red color of the "bole" underneath the gilt layer; whereas, Figure 2b was caused with aeroplane polarized lite in order to highlight the gilded surface.

Figure 3. OM view of the cross-section at different magnification objectives: (a) twenty× with cross polarization; (b) xx× with plane polarization; (c) 100× with cross polarization; and (d) 100× with plane polarization.

Effigy iii. OM view of the cross-department at different magnification objectives: (a) xx× with cross polarization; (b) 20× with aeroplane polarization; (c) 100× with cross polarization; and (d) 100× with plane polarization.

Effigy four. (a–c) are the BSE-SEM images of the gilding at different magnifications. In some parts, the distribution of the uppermost layer was not directly just folded covering the lower layer as it tin can be observed more clearly in the high-magnified figures b and c.

Effigy iv. (a–c) are the BSE-SEM images of the gilding at different magnifications. In some parts, the distribution of the uppermost layer was not straight but folded roofing the lower layer equally information technology tin can be observed more conspicuously in the high-magnified figures b and c.

Effigy 5. BSE-SEM image of the gilding and EDX spot analysis on 2 dissimilar layers.

Figure 5. BSE-SEM image of the gilding and EDX spot analysis on two different layers.

Figure half dozen. EDX elemental map of the gilding.

Effigy 6. EDX elemental map of the gilding.

Figure 7. BSE-SEM prototype of the gilding and EDX spot analysis on two unlike layers.

Figure 7. BSE-SEM image of the gilding and EDX spot analysis on 2 different layers.

Figure viii. BSE-SEM image and EDX spot analysis on corrosion products grown over the thin gold layer.

Effigy viii. BSE-SEM prototype and EDX spot analysis on corrosion products grown over the thin gold layer.

Effigy nine. (a) micro-ATR-FTIR spectrum of the "bole"; (b) micro-Raman spectrum of the ground layer.

Figure ix. (a) micro-ATR-FTIR spectrum of the "bole"; (b) micro-Raman spectrum of the ground layer.

Table i. Semi-quantitative EDX elemental analysis of the gilding layers.

Table i. Semi-quantitative EDX elemental analysis of the gilding layers.

| Element | Shell | Weight% | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 5 | Figure 7 | Figure eight | |||||

| Spot 1 Gold Layer | Spot 2 Silver Layer | Spot 1 Gold Layer | Spot 2 Silverish Layer | Spot 1 Argent Degradation | Spot 2 Golden Underneath Silver | ||

| O | K | 10 | 28 | 5 | 6 | 9 | 21 |

| Mg | One thousand | 1 | i | / | / | <1 | <i |

| Al | 1000 | one | 5 | / | / | one | 2 |

| Si | K | 2 | vii | / | 1 | / | 3 |

| Cl | 1000 | 3 | 9 | / | 8 | ii | 1 |

| Ag | L | 19 | 42 | 15 | 81 | 72 | 42 |

| Ca | K | one | 1 | / | / | / | / |

| Fe | K | 3 | iii | / | / | / | 1 |

| Cu | K | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 1 | one |

| Au | L | 59 | 3 | 76 | / | / | 19 |

| S | / | / | / | 16 | 9 | ||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2571-9408/2/2/76/htm

0 Response to "Florence Italy Arte De Medici E Degli Spezial a Vallecchi 1922"

Publicar un comentario